New York Rangers analysis: On PDO, puck luck, and shot suppression versus quality shot suppression

The Rangers difficult start was a factor of a few things, but to simply call it "bad luck" is leaving out a lot of context.

Let's begin with the obvious: Since getting off to a 1-3 start, the Rangers have seemingly corrected many of the problems that fueled said stint. Three consecutive wins against the Hurricanes (whoop dee doo), the Sharks, and the Devils, and the Blueshirts appear to be back on track, especially as they await the returns of Derek Stepan and Dan Boyle.

But something interesting happened during those poor four opening games, something that requires a bit more exploration.

Seventeen goals against in three games

Chief among the Rangers issues through the team's first 240 minutes of hockey was the number of goals it was allowing. Take away the season-opener against the Blues (a win anyway), and the Rangers conceded 17 goals in three games. For a team that's finished in the top five in goals against for the past four seasons, it was a puzzling trend, and one that many assumed would come to an end, and likely coincidence with what was also considered an inevitable turnaround.

Of course the goals against weren't the only problems the team faced. The power play was non-existent, there were those aforementioned key injuries, and virtually anyone not named Rick Nash wasn't scoring goals.

Heck, some felt the Rangers were just plain unlucky.

The concept of luck, and how it pertains to hockey, isn't so cut-and-dry, but is clairvoyant in a sense. When it comes to the pendulum of luck, we use a statistic called PDO (it's not an acronym because it stands for nothing), which is contrived by adding a teams on-ice save percentage with it's on-ice shooting percentage. An average PDO is considered right around 100, and conceptually, the idea is if your PDO is below 100, you may be experiencing some bad luck, and that number should regress toward the mean. Likewise, teams with a PDO above 100 are due for a reality check (see: the 2012-13 Maple Leafs, and likely the 2013-14 Avalanche).

After their fourth game of the season, the Rangers PDO sat a lowly 93.1%. Only the Oilers came in with a lower number. Sure, maybe the Rangers were absent some luck in those three losses, but in contextualizing that start, and specifically how PDO played a role, to simply cry "bad luck" is leaving out a lot of the story.

Luck can be created through meticulous defending

The first place to begin is how ineffective a statistic like PDO can be in such a small sample size. Even had the Rangers won, let's say, three out of four of those games, and one loss in which the team allowed six goal would have thrown things very much out of whack because of the horrid save percentage that comes with it.

But the Rangers weren't allowing five and six goals a night because they were down on their luck; they were allowing five and six goals a night because of uncharacteristically subpar goaltending, and lax coverage from both their defensemen and forwards.

In Rangers three wins this season, Lundqvist has .966 save percentage. In three losses, he has a .738 SP.

— Ken Campbell (@THNKenCampbell) October 20, 2014 PDO was without a doubt a convenient scapegoat to a 1-3 start, especially if the end point was that the remedy for the Rangers was just to get luckier. New York wasn't scoring a ton (2.5 goals per game), but had an on-ice sh% around 10. That number wasn't the problem, especially considering the team shot 6.66% overall in 2013-14.

The issue again was what the Rangers were giving up, which wasn't a problem that would correct itself out of a concept as obscure as luck. In the three games the team has won since then, the Rangers have given up a combined five goals in close to 190 minutes of hockey, or over three times fewer than the three-game losing streak that directly preceded the turnaround.

That shift hardly lucky.

Limiting quality chances, and not just chances

By this point, we all know that puck possession is paramount to winning. In saying that, a team's ability to suppress shots is directly linked to its ability to drive possession. When we use Corsi as a proxy to judge how frequently a team has the puck, and Corsi is measured by shot attempts, the link is made.

Quality versus quantity is somewhat a polarizing argument among hockey circles. Most teams that are successful in the standings are leaders in statistics like Corsi and Fenwick, ones that measure volume, and not quality. It was something that was explored in SB Nation's preview for the Anaheim Ducks this season:

In a league that has increasingly valued shot-based metrics, the Ducks have regularly been an outlier, making the playoffs despite not posting strong Corsi or Fenwick numbers. Last year Anaheim had eight players score on better than 10 percent of their shots. While 'quality' is a bit of an amorphous, hard to define term, the Ducks have been consistent in taking and converting on their chances.

Getting back to the Rangers four-game start, the team allowed 99 Corsi events against in score-close situations. Over the three-game winning streak that number shrunk at 84, although it's important to note that the Rangers played close to a full game's worth of minutes over those first four games in non-score close situations.

If a team could give up no shots, it would win every game, but that will never happen. Then there are rare games when a team completely dominates in shot attempts, yet ends up losing. Limiting shots is very important, but there's also something to be said about limiting quality scoring chances.

As far as what the Rangers were giving up, there wasn't a major difference in shot suppression when the team was winning versus when the team was losing. What it came down to, in the end, was the quality chances it was allowing its opponents to generate.

Brad Penner, USA Today Sports

Brad Penner, USA Today Sports

Gap control , zone spacing, and 5v5 coverage

A team's ability to suppress quality scoring chances is a five-man effort. It isn't simply the responsibility of the defensemen, and while the Rangers blue liners certainly needed to play better than they had when the team was losing, the forwards weren't helping out much either.

It's something both Lee Stempniak and Carl Hagelin expressed to The Daily News:

"We were shying away from hits on the forecheck," said Stempniak, who had two goals and an assist through the Rangers' first three games. "We sort of flew by, maybe put a stick in there, but never really committed."

Left winger Carl Hagelin said the forwards' lack of focus put their defensemen in impossible positions.

"We weren't just failing to finish checks, we were taking big turns (skating in a half-circle before turning back), and that's how you put yourself in no man's land," Hagelin said. "The D-men have to read off that, and they might get tentative because they don't know what to do. Then you have guys trying to do each other's jobs, and it breaks down."

The Rangers were sagging off puck-carriers, and giving up too much space to shooters in the offensive zone. All that creates is extended shifts spent defending, chasing the puck, and eventually, an avalanche of poor spacing.

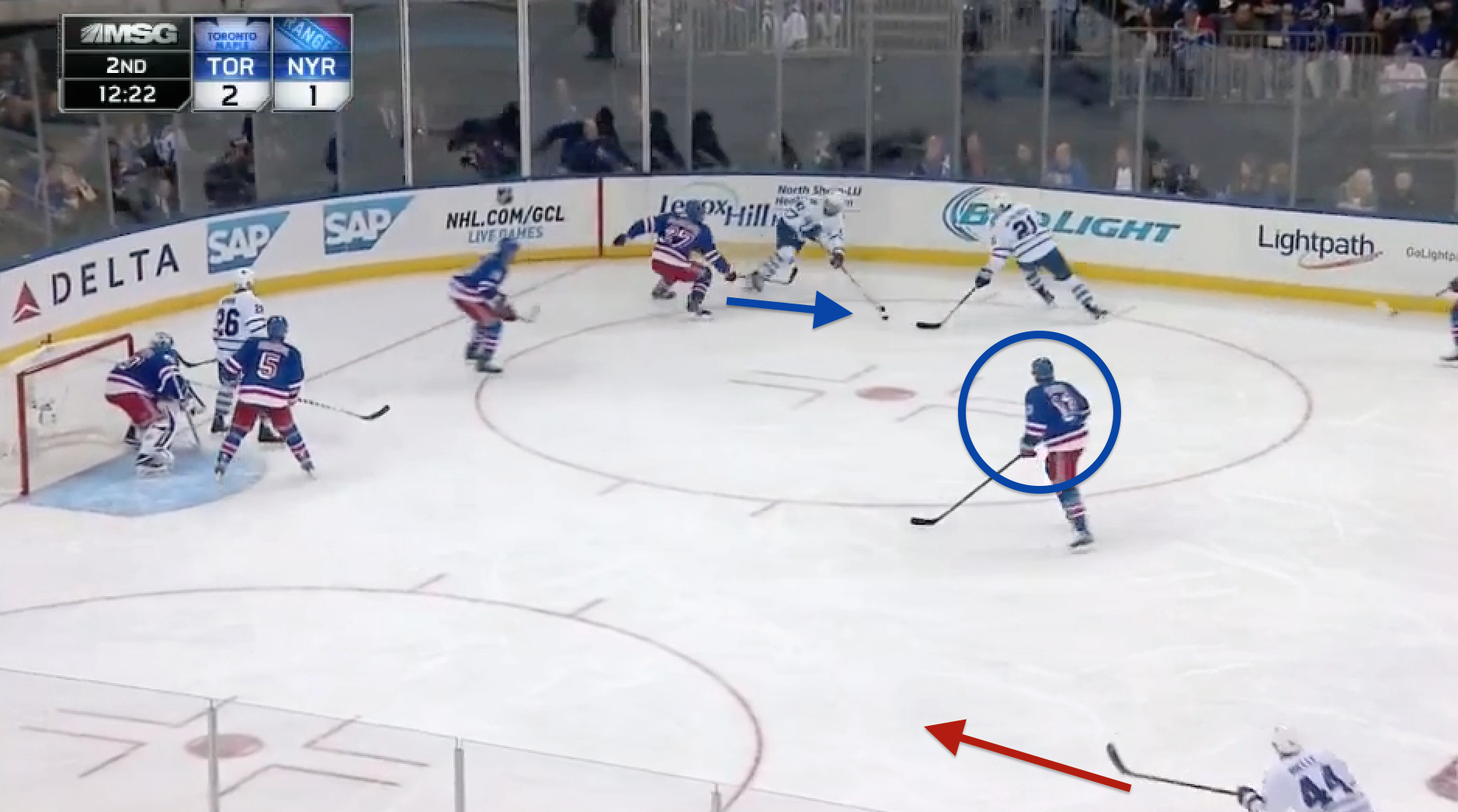

On this goal Nazem Kadri scored agains the Rangers, New York's forwards give up a ton of space, and eventually, it turns into a goal against.

This sequence begins with the puck getting worked around the wall to Kadri. Both Hagelin and Kevin Hayes are in the vicinity, but Hagelin is peeling off to cover the point, while Hayes is pointing down low toward another man. This goes hand-in-hand with what Hagelin was saying: as Kadri retrieves the puck, there's no one there to pressure him, and he's allowed to turn and see the play cleanly.

Ryan McDonagh is forced to rotate toward Kadri, while all he can do is reach with his stick. Hayes is now in the middle, kind of playing a free safety role and at the moment, at least defending against a cross-ice pass for Morgan Rielly.

Now the breakdowns really begin. Kadri and James van Riemsdyk cross along the wall, and McDonagh is still reaching for the puck, while Hayes' spacing is thrown off by Kadri's movement, and there's a clear lane to get the puck to Rielly.

As Rielly accepts the pass, this is another example of a Rangers forward giving up too much space. Hayes is getting picked on a lot here, but he concedes too much ice to Rielly, and doesn't do a great job of getting in the shooting lane.

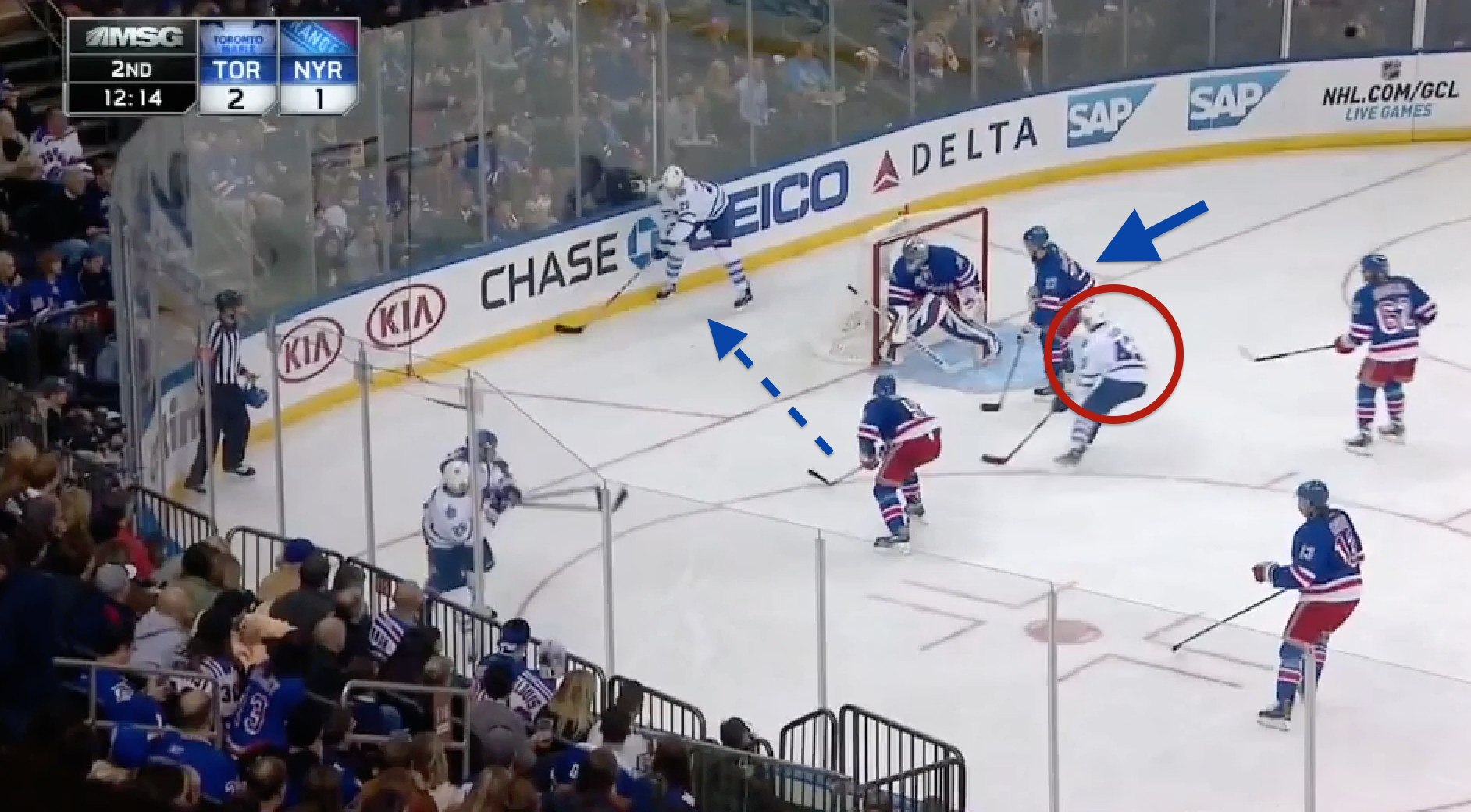

The shot comes in and hits Dan Girardi. van Riemsdyk ends up with the puck behind the net, with Girardi and McDonagh positioned at each post. Kadri is planted between them, and only one player should go down to hound van Riemsdyk, while one should remain in front with Kadri.

But both Girardi and McDonagh try to make a play on the puck, leaving Kadri all alone above the crease. It's not only a coverage breakdown, but a communication breakdown, as Hayes, Hagelin, and J.T. Miller are left defending areas of the zone where the puck isn't, while none of them made a move toward Kadri.

This goal was pretty emblematic of the Rangers start. There were mistakes made by the forwards, which led to more pressure on the defensemen, and mistakes in turn just about everyone on the ice. Henrik Lundqvist had no chance at stopping the shot, and the low sv% he would finish the game with, directly effecting the team's PDO, wasn't a factor of bad luck, but bad in-zone play.

This isn't to say to notion that PDO represents luck is entirely askew. It's just providing context, and breaking down how isolated miscues, of which there were many during the Rangers poor start, were really the catalyst of the team's problems. Good teams will be able to to manage their opposition's shot volume through strong possession. As a unit, the Rangers had the 11th-fewst Corsi events against last season, and it comes as no surprise that, for the most part, teams that are able to minimize how many shots against they see are strong in possession.

(Out of the top 10 teams in terms of fewest Corsi events against in 2013-14, only the Blue Jackets and Wild had a CF% below 50, and of the top 10 teams, on the Panthers and Devils didn't make the playoffs.)

What plagued the Rangers during their first four games wasn't bad luck, or shot suppression per say, it was that when the team was giving up chances, they were in dangerous areas. When the Rangers beat the Sharks they allowed 33 shots on goal and 58 total (keeping in mind that's including three Sharks power plays, and over an entire period of non score-close situations), but Lundqvist didn't face many, truly difficult chances.

In the end, a combination of the Rangers goalies playing better, complemented with a stronger, combined effort from both the defensemen and forwards is what buoyed the Rangers PDO back to reality. That number currently sits at 99.8%, a full six points higher than it was after the loss to the Maple Leafs. For reference, the Rangers PDO last season finished at 99.7%.

What's seen the Rangers navigate another slow start is the team creating its own bounces, and its own luck, and not waiting for its play to regress simply because it was meant to on paper.

All stats via War on Ice, Progressive Hockey, and Hockey Analysis